When faxes, phone boxes and mixtapes were the language of love and connection.

I’ve just come back from five days of solo hiking in the Stirling Ranges National Park in Western Australia. Once you leave Perth and start driving south-east, phone reception drops away fast. You might get the occasional flicker of 4G when you pass through one of those blink-and-you’ll-miss-it roadhouse towns – a single bar of service beaming from the lone tower on a scrubby hill, before it vanishes back to nothing.

By the time you’re six hours out of Perth and deep in the national park, “no reception” actually means no reception. The Airbnb cabin I stayed in – blissfully – had no Wi-Fi and only one bar of 4G signal if I stood on top of the toilet, arm stretched out the window like some kind of desperate antenna.

The quiet was almost offensively loud at first – like my brain didn’t know what to do with all its new bandwidth. Then, it quickly became a salve; completely medicinal. Without the constant tug of a digital connection, I started to remember what stillness feels like: how thought arrives uninvited, how creativity stretches its limbs again, and how memory, slow and unhurried, slips back in through the side door.

Somewhere between the silence and the long solo hikes up remote, wind-beaten peaks, I found myself remembering what life used to feel like on the Australian rowing team in the 1990s. We’d travel for months at a time – training and racing across Europe, sometimes Canada, sometimes the States – completely sealed inside a bubble with no tether to the outside world. And somehow, that absence of connection made us more connected than ever.

We’d usually travel for around three months straight, swapping each Australian winter for a European summer (a massive perk of the job). Same teammates, same long-winded banter over every meal, and an endless stream of crew-versus-crew practical jokes that escalated week by week. We shared everything – hotel rooms, headphones, books, music, buses, trains, planes, meals, secrets, and moods. There was no Wi-Fi, no email, no social media. Just us, our gear, our rituals, and each other. Truly a case of what goes on tour stays on tour.

To phone home was always a bit of a fiasco. You’d have to wander over to the Bahnhof or hunt down one of those 1990s phone booths you only ever found in places like Switzerland – fancy as fuck, lined in timber, almost soundproof, complete with a little metal ashtray so one could light up and charf a sophisticated Euro-dart while getting down to business on the payphone – if one so wished.

Then came the ritual: reverse charge call or, more often, the convoluted process of plugging in a dozen digits from an international calling card just to finally connect back to loved ones in Australia. That was it. Apart from the odd silly postcard or a long-winded handwritten letter home, that weekly phone call was the only tether to the outside world.

What strikes me now is how completely and utterly – and luxuriously – undistracted we were. Everyone was just there. Fully in it. No one sitting at dinner with their head buried in a phone (like I sadly see everywhere these days – and yes, I know I sound like a nana, and no, I don’t give a fuck. It’s bullshit). We weren’t posting moments; we were living them. In real time. I know – so fucking old school.

When there was downtime – and there was a lot – travelling across countries by train, lolling about by lakes, meandering around airports, or waiting for the bus at some regatta centre in the middle of nowhere, no one was lying around zombified with a phone glued to their hand. We kicked a ball. We traded banter. We upped the ante on the running jokes that lasted entire seasons. We caught a few zzz’s, read, or joined in the constant back-and-forth humour that was juvenile and perfect.

We lived in a self-contained, oxygen-rich bubble of presence and connection. That kind of intimacy builds bonds you can’t replicate in group chats, team apps, or so-called online communities. It was real human texture – boredom, laughter, irritation -all of it shared, unfiltered. IRL.

And it made me realise, out there in the quiet stillness of last week’s hike, how much I’ve missed that – and how rare it’s become. I mourn that time now: the simplicity, the authenticity, the unspoken ease of real human connection we all took for granted. We had no idea what was coming – the human-connection-and-attention hand grenade that would land in the mid-to-late 2000s, blowing up our relationships, our focus, and our ability to just be. Cue social media, then smartphones.

Love. 1990s vs. Now

A couple of weeks ago, in one of my random moments of weakness (or curiosity, or both), I set up a profile on Bumble. I hate dating apps almost as much as I hate social media – the swiping, the superficiality, the pathetic little dopamine hits. It’s all so painfully goddamn ick.

But as much as I loathe them, I try to stay open-minded. Apparently, this is how people meet now (insert vomit emoji). And to be fair, when I’ve managed to overcome my ick and have cracked one open, I’ve met some genuinely cool and interesting people – a few of whom have turned into lifelong friends.

Like Pierre, my beautiful Swiss mate (and former lover) – my very first ever Tinder date – back in Canggu, Bali, in 2018. What started as an impulsive swipe led to a drink turned into an international whirlwind romance that traversed the globe several times over. Seven years later, we’re still close mates. I even took my boys snowboarding in Switzerland this January, and we stayed with Pierre at his family’s old-school chalet in Verbier – the kind with creaky timber floors, fondue for lunch, and views that look like a Toblerone box. So yes, I suppose I have to say it (through gritted teeth) thanks, Tinder.

So, I remind myself of stories like that – see Rach, it’s not all bad – which is why, every now and then, I go “ah, fuck it” and dip a toe back in.

Typically, I’ve preferred using dating apps when I’m travelling, mostly in Indonesia where I spend a lot of time. The melting pot of people there – open-minded travellers, digital nomads, expats, adventurers – they’re just much more my kind. Open, curious, alive.

Open a dating app in Perth, though? Christ on a bike. You need to be mentally fortified for what comes at you: a sea of fluorescent-clad FIFO workers, wild beards, red dust, and jet skis. Men with giant dogs licking their faces in their Toyota Hilux’s. Or the BCF uniform crowd – fishing shirts, Bunnings straw hats, blue-lensed polarised sunnies, beer guts, and bloodied dead fish held proudly to camera.

Yeah, I know I sound like a bitch – and yes, I’m wildly stereotyping – but fuck me, it’s a thing. It’s hardcore. And it’s Ewww.

Annnyyyywaayyy, I digress. Let’s get back to this latest example.

A few weeks ago, I went on a date with a nice, normal-looking guy – sans fish – who I’d matched with after my new Bumble profile went live; and breaking from my usual pattern, this one was in Perth, of all places.

We met for a coffee that quickly turned into three hours of real connection: face-to-face, deep conversation, proper laughs, vulnerability. Huh, I thought. This guy’s actually refreshing. He seems… cool.

In the weeks that followed, we went on two more dates – same deal. Time slipped into a vortex of something that felt authentic, human, genuine, real. Hours of great conversation, laughter, and even, yes, possibility.

Then…

Crickets.

Silence.

Ghosted.

A word that didn’t even exist in the 1990s. Neither did breadcrumbing, love bombing, or any of the other linguistic band-aids we now use to sanitise what is, frankly, emotional cowardice. All by-products of digital disconnection dressed up as romance.

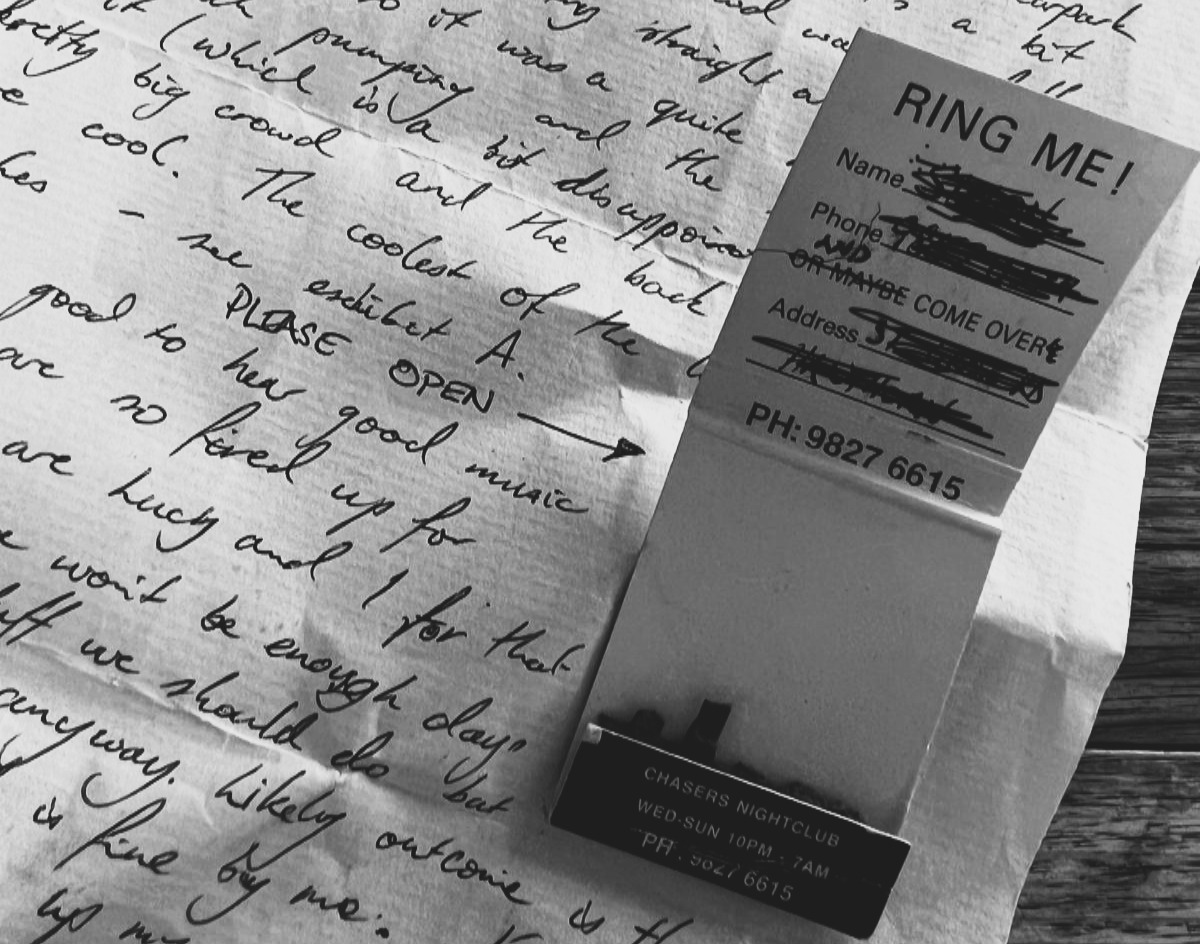

Back in the 90s, if you had a fling, a crush, or a full-blown love affair, you were accountable to it. Because connection took genuine thought, creativity and effort.

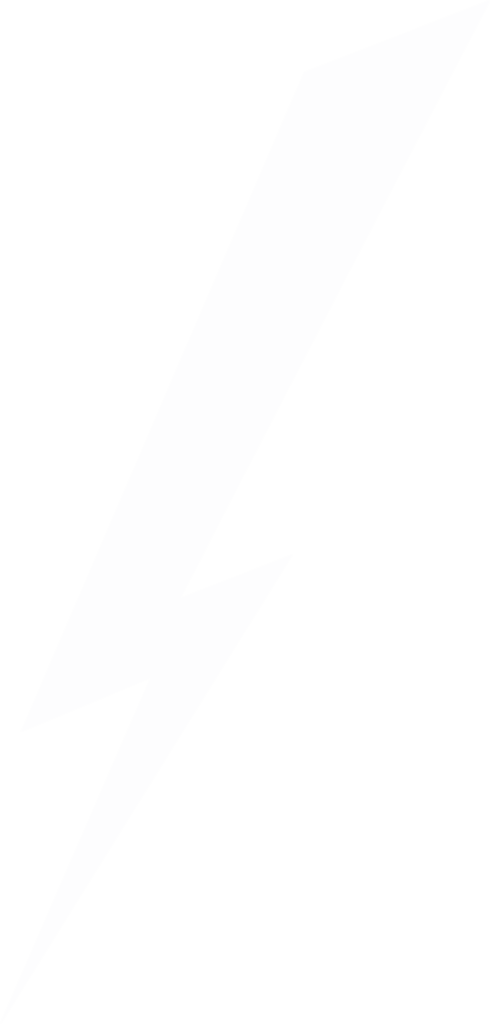

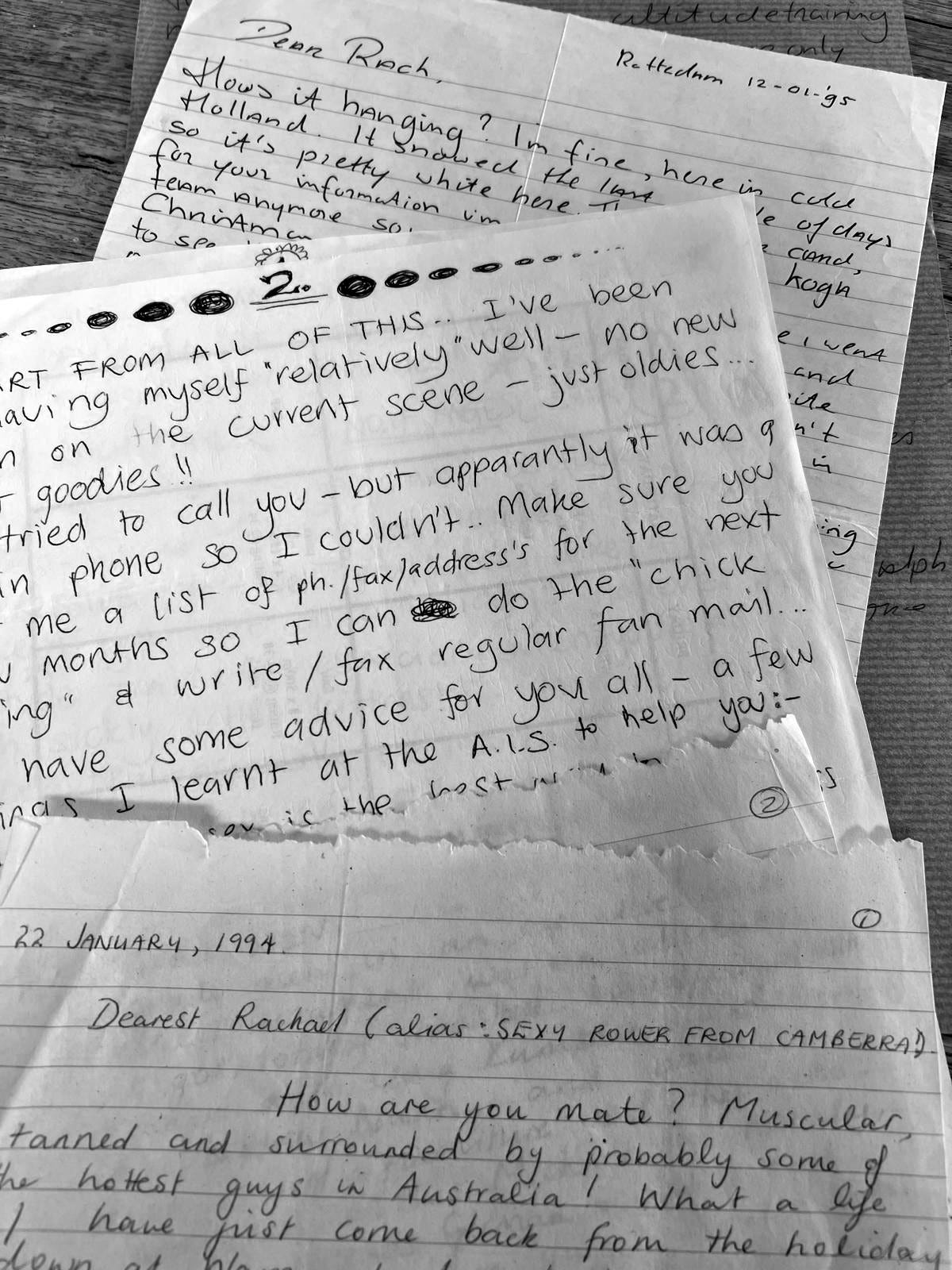

I remember one in particular, a long-distance romance in the mid-1990s. He was a professional cyclist – and he knows who he is 🙂 We were both young athletes, both constantly on tour, training and competing in different corners of the world. There was no WhatsApp, no Snapchat, no Instagram. We had just phone boxes and fax machines.

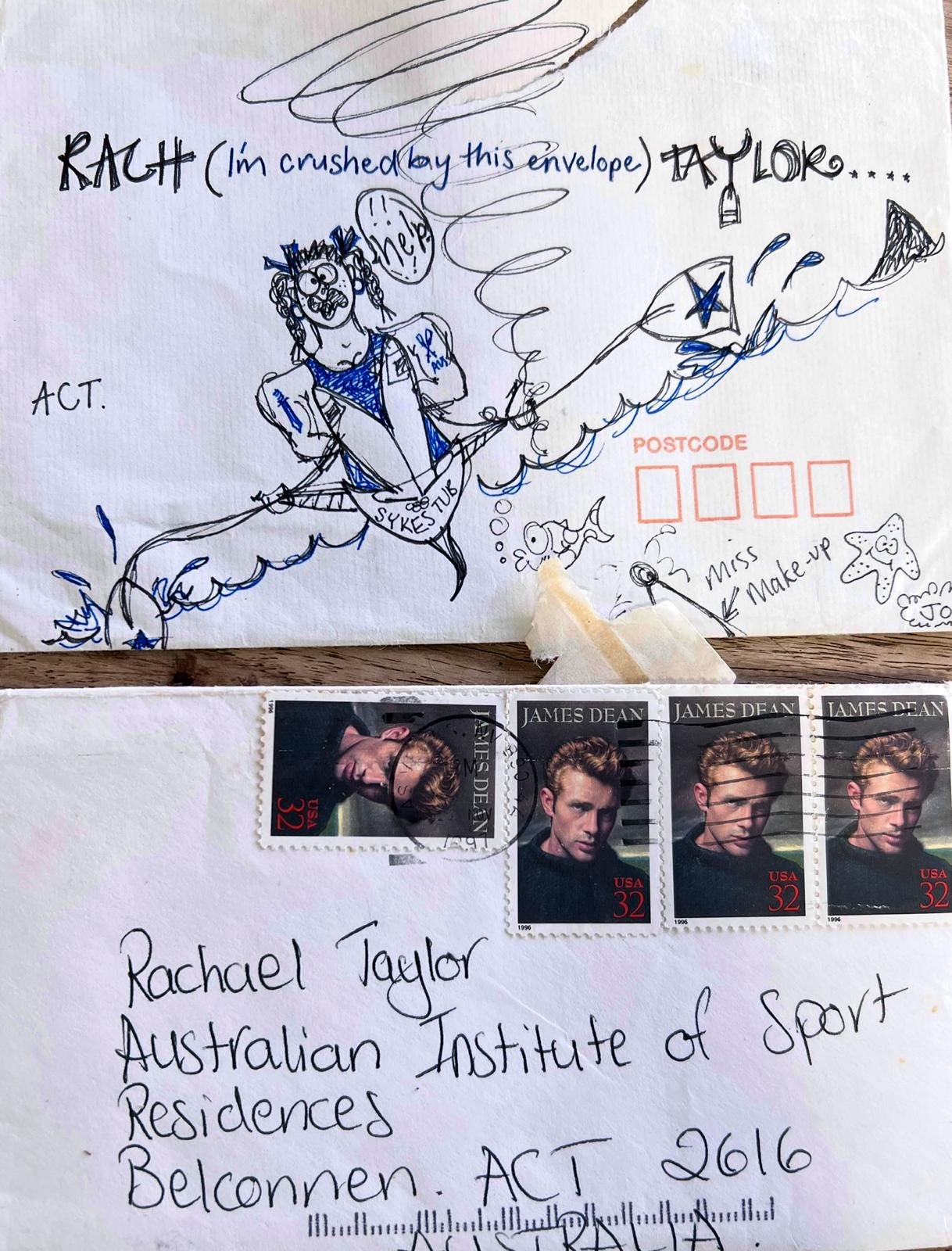

Before heading off to training camps or overseas tours, we’d swap schedules: which dates, which cities, which hotels, which fax numbers. Then when we were away – sweaty after each morning training session – I’d head straight to hotel reception and ask, in some mangled Italian, “Any faxes for room twenty-two?”

If there was one, it came rolled up like a tiny scroll – that perfect smell of warm ink on curling paper. My heart would skip a beat, and my teammates would give a knowing smile as I (ok, maybe we) poured over the facsimile whilst drinking black coffee dunked with dry biscotti at breakfast.

Sometimes, a package with a letter and a burned CD would arrive. We loved the same music – Dinosaur Jr, Ministry, L7, Smashing Pumpkins, NIN, Beastie Boys – so we traded mixtapes like it was its own love language.

The silence between those moments mattered. Waiting for a fax, a letter, a call – it built anticipation, imagination, longing. You couldn’t wait to finally see the person again, in real life.

That was 1990s connection. Slow, intentional, creative, romantic. And fucking great fun.

There was no decoding the tone of a barrage of allegedly seductive WhatsApp messages, no overanalysing or trying to interpret intent. And there sure as hell weren’t any dick pics. Ewwww, mate! (That’s another topic altogether.)

You couldn’t love bomb nor ghost someone via fax. Neither would you. It just wasn’t the way things were done. When things ended, people said so – usually face to face, or with a sincere phone call that took a lot of courage to make. Because that was the only way to do it. There was honour in that constraint. Honour that now feels all but lost.

As you can imagine, there was plenty of romantic cross-pollination during the international regatta season each year. As national team athletes, we all knew who was who in the zoo – which hotties were on which team, and in which boat class. It wasn’t uncommon that after the first World Cup after-party, a few new inter-team romances would kick-off.

Then came the waiting. Unless you’d already graduated to swapping fax numbers or scribbling hotel names and dates, you might not see them again until the next World Cup regatta – weeks later, maybe months. But when you did, you’d recognise them instantly across the boat park. A look. An awkward blush. A half-smile. Teammates nudging you in the side and sniggering. A shared secret that had lived quietly in your chest all that time.

Then came the challenge: finding a moment – in the absolute non-privacy of a boat park filled with every national team in the world – to “accidentally” bump into your romantic tryst and organise an actual date. A coffee or a drink. In real life. Face to face. Yeah, that’s right – you had to actually talk to them. In the flesh. Hahaha. Those were the days.

We talk about “slowing down” now like it’s some kind of lifestyle status symbol. But back then, slow was the default. It was built into the mechanics of connection and communication. You put in effort. You had to wait. You had to wonder. You treasured opportunities. And maybe that made connection mean more. It certainly felt like it.

Now? We’re drowning in half-connections. Random connections. Contrived communities. We can group chat with twenty people and not truly connect with a single one of them.

Even love has become something we outsource to algorithms. We call it matching, but it’s really just the monetised outsourcing of chemistry to code.

And the worst part? Younger generations think this is normal. The behaviour that comes with it – trolling, ghosting, breadcrumbing, the slow erosion of basic decency – we treat that as normal too; like it’s been around forever. But it fucking hasn’t.

I keep thinking about how human behaviour has deteriorated simply because the medium allows it. Accountability, effort, and the delay between impulse and action has disappeared – and with it, our capacity for real connection, reflection, and respect.

A Sea of Phones

My fifteen-year-old son went to his first big gig a few weekends ago – an all-ages rap event in Perth. He was stoked. His first real live music experience. I remember that thrill so vividly – the sweat, the bass, the surge of something electric and alive, jumping in a mosh pit with your best mates, feeling like you belonged to the moment.

He showed me some videos afterwards. The music sounded incredible, the crowd was going off – but every single person in the audience was holding up a phone. Thousands of tiny screens documenting what no one was actually living. It looked less like a concert and more like a cult-like digital vigil – a sea of followers standing in unison, glowing screens raised to the sky, all pointed at the stage.

Next week, I’m taking both my sons to see Metallica. I can’t wait. But I’m also bracing for the sea of phones that will glow like a thousand tiny suns over the crowd. It just is what it is. Welcome to our farked up Brave New World.

I don’t want to sound like a cranky old Luddite (too late Rach) – I love much of what tech enables. I use it. I rely on it too, just like we all do. But I can’t help wondering what my boys are missing out on. Actually, that’s not true. I already know what they’re missing out on – and I’m already mourning it.

The thrill of genuine discovery. The joy of being in a bubble on the other side of the planet, unreachable. The alchemy of real-time connection that isn’t filtered, posted, curated, or timestamped. They’ll grow up knowing everything but connecting less.

They’ll never know what it’s like to backpack through Europe with only a dog-eared Lonely Planet guide and a fist full of maps – no itinerary, no bookings, no TikTok recommendations, no queues of Instagrammers all dressed the exact same, like lemmings, waiting to take the one photo at the one place every motherfucker visits for that same fucking reason (Ahhh, shoot me).

No – we were lucky enough to travel the world relying on serendipity and chance. Meeting strangers on trains, because no one had phones to zombify them. People looked out the window, daydreamed, or chatted with the person in the booth next to them.

Random interactions turned into drinks, dinners, shared hostel rooms. One conversation could lead to a night of chaos, solving the world’s problems over sangria and hashish, getting gloriously lost in the back streets of Barcelona. Those hilarious unscripted interactions led you to places – and people – no app could ever have recommended. No online reviews. No curated feeds. Just human energy – connection, curiosity, trust, and luck.

That’s how friendships were formed. How romances sparked. How we found the next chapter of the story.

Echo of the Analog

Being alone in that cabin in the Stirling Ranges last week – no Wi-Fi, no phone service – I remembered what it feels like to actually be in my own company. To think things through. To aimlessly daydream. To metabolise feelings. To read uninterrupted. To laugh out loud at memories from years gone by.

In that quiet, my body slowed down enough for reflection to begin. That’s the thing most of us have forgotten. Without silence and stillness, there’s no space for thought – or feeling – to take shape.

I reconnected with myself. Properly. Not through meditation apps or journalling prompts, but through absence. Through doing nothing. Through being unreachable. And I realised: that’s the rarest kind of connection we have left.

We talk a lot these days about optimisation – mental health, performance, productivity – but not nearly enough about the true quality of our connections. We’ve mistaken contact for closeness.

In the 90s, we had fewer ways to reach each other, but when we did, we reached much further.

Those long European tours. Those faxed love letters. Those blurry nights in unfamiliar cities. They weren’t perfect – although from where I sit now, they sure feel like they were. But you know what they were? They were real. They required us to show up. They demanded time. Effort. Presence. Built-in and assumed honour and integrity.

When I came home from the hike, my phone buzzed back to life – dozens of messages, notifications, updates. It felt like static. And I thought of those fax machines, those handwritten love letters, those nights in foreign rooms where we were unreachable but completely alive, where we genuinely knew ‘everyone else can wait’.

We now live in a culture that sanctifies both ‘connectivity’ and independence. In much of the Western world, individualism has become our civic setting. But let’s not forget this is a cultural construct, not our nature. Biologically, we are communal. We co-regulate, mirror, nurture, and survive together.

To live severed from others is not evolution – it’s deprivation. Yet modern life conspires to make this disconnection seem normalised, almost respectable.

Work has migrated online. Classrooms have emptied. Human faces replaced by glowing rectangles. Covid amplified it. What was once shared rhythm – commuting, gathering, sport, play – has become private scheduling and solo-phone-zombification-on-the-couch.

We meet through screens, mute when tired, and tell ourselves this is connection. A society optimised for communication efficiency, but one that has forgetten how to belong. The nervous system, deprived of real proximity, forgets what safety, love and support feel like in another’s presence. The species devolves.

The results are visible everywhere: an epidemic of loneliness, of social anxiety, of people surrounded by contacts yet starved of real connection. The irony is that we’ve never been more connected technologically, yet never more isolated emotionally – nor more tolerant of the half-baked, low-effort, and frankly bullshit ways we now mistake for communication.

And that, I think, is the quiet tragedy of it all – we’ve devolved into a world where reaching is effortless, but truly connecting feels almost impossible.

Rant over.

Rach Taylor is a high-performance career and life coach, life after sport and athlete transition coach, wanna-be-DJ, speaker, Olympic medallist, and former senior HR guru leader. Rach brings Olympic-level insight, real-world HR and leadership scars experience, a geeky obsession with human optimisation, and a no-BS, heart-led approach to every space she plays works in. Based in Perth, Australia. Working with clients and collaborators globally.